What is Sympathy?

See also: Dealing with Bereavement and GriefSympathy is feeling bad for someone else because of something that has happened to them.

We often talk about it and feel sympathetic when someone has died, or something bad has happened, saying ‘Give them my sympathy’, or ‘I really feel for them’.

As a concept, sympathy is closely connected to both empathy and compassion. You may find our pages: What it Empathy? and Compassion useful too.

Sympathy, Empathy and Compassion

What is the distinction between sympathy, empathy and compassion? The words are often used interchangeably, but they do have important differences.

Some Working Definitions

sympathy n. power of entering into another’s feelings or mind: … compassion

empathy n. the power of entering into another’s personality and imaginatively experiencing his experiences.

compassion n. fellow-feeling, or sorrow for the sufferings of another

Chambers English Dictionary, 1989 edition

These definitions, however, do not necessarily help to establish the difference. It may be helpful to look at the origin of the words.

Sympathy comes from the Greek syn, meaning with and pathos, or suffering.

Compassion is from the Latin com, meaning with, and passus, to suffer.

In other words, sympathy and compassion have exactly the same root, but in different languages.

Empathy also comes from the Greek, from en meaning in, and pathos, again for suffering. There is, therefore, a much stronger sense of experience in empathy.

Sympathy or compassion is feeling for the other person, empathy is experiencing what they experience, as if you were that person, albeit through the imagination.

As our page on Compassion argues, however, there has come to be an element of action in the use of the word compassion which is lacking from sympathy or empathy.

A feeling of compassion, then, usually results in some action, perhaps donating money or time. Sympathy tends to begin and end with fellow-feeling, or ‘expressing your sympathy’.

Causes of Sympathy

For people to experience sympathy towards someone else, several elements are necessary:

You must be paying attention to the other person.

Being distracted limits our ability to feel sympathy.

The other person must seem in need in some way.

Our perceptions of the level of need will determine the level of sympathy. For example, someone with a graze on their knee will get less sympathy than someone else with a broken leg.

We are also much more likely to be sympathetic towards someone who appears to have done nothing to ‘earn’ their misfortune.

The child who falls while running towards a parent will get more sympathy than the one who was doing something that they had been specifically told not to do, and has fallen as a result.

Sympathy in Healthcare

The tendency to feel more sympathy towards those who did not ‘deserve’ their problems can be a major problem for healthcare workers. There is a tendency to feel less sympathy to those suffering from ‘lifestyle’ diseases, such as diabetes resulting from obesity, or lung cancer after a lifetime of smoking, than those who have contracted similar diseases with no obvious cause.

Healthcare workers, and others, need to fight against this tendency, because we are all human, and all equally deserving of care and support during difficult times.

The level of sympathy is also likely to be affected by the specific circumstances.

We are generally more likely to be more sympathetic towards someone who is geographically closer than someone on the other side of the world. This is spatial proximity.

We are also more sympathetic towards people who are more like us. This is referred to as social proximity.

Furthermore, we are also more likely to be sympathetic if we have experienced the same situation personally and found it difficult. However, ongoing exposure to the same or a similar situation will dampen sympathy.

For example, the first time we see pictures or hear about an earthquake, we may be motivated to donate money to relieve suffering. If, however, there is another earthquake elsewhere a few days later, we may feel less sympathetic, a situation sometimes referred to as compassion fatigue.

Showing Sympathy

Because sympathy is indelibly linked to bad experiences, for example, the death of a family member, it is often appropriate to show your sympathy with someone else.

While this can seem like a formality, the idea is to help the other person to feel better, by showing that you understand that they are having a bad time, and may need some help.

Sympathy may be expressed either verbally or non-verbally.

Examples of sympathy expressed verbally include:

- Speaking to someone to say how sorry you are about their situation; and

- Sending a card when someone has been bereaved.

Examples of sympathy expressed non-verbally include:

- Patting someone on the shoulder at a funeral;

- Putting a hand on someone’s arm when they tell you their bad news; and

- Dropping your tone of voice when you speak.

For more about this, see our pages on Non-Verbal Communication

Showing Sympathy Appropriately – Ring Theory

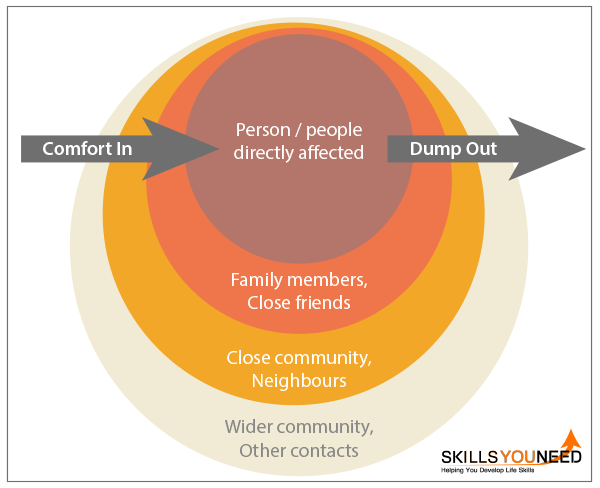

A few years ago, psychologist Susan Silk and mediator Barry Goodman devised a simple diagram to help people to respond appropriately to grief, affliction or problems in their own and other people’s lives. They called it Ring Theory.

The idea is simple. Imagine a series of concentric circles. In the middle circle is the person or people who are most directly affected by the trauma. In the next circle are their direct family and closest friends. Outside them are more distant family and friends, then acquaintances and so on. You can have as many circles as you need.

The person at the centre of the circle can say what they like to anyone. They can vent at any time, or in any way. Those beyond that, however, can only vent OUTWARDS. Inwards, they need to express sympathy and provide comfort.

The rule is simple: Comfort In, Dump Out.

If you stick to that rule, you will be able to provide sympathy effectively, and also vent your concerns in an appropriate way, to those who can best help you to deal with them.

Sympathy is innate, but it is also learned

Children as young as 12 months old have been observed to show sympathetic behaviour, for example, giving their parents a toy without being prompted, or crying when another baby cries. These are very basic sympathetic responses. Some children are inherently more social and sympathetic.

However, as children learn and develop, their ability to feel sympathy also develops as they learn from their parents and others around them. Given that adolescents are often described as exhibiting selfish behaviour, it seems likely that ability to sympathise continues to develop throughout childhood and adolescent, and probably into adulthood as well.

This means that it is possible to develop your ability to feel and express sympathy even as an adult.

Continue to:

What is Empathy?

Compassion