Dealing with Bereavement and Grief

See also: SympathyUnfortunately, we are all going to die sometime. This also means, of course, that by the law of averages, we are also all going to be bereaved several times during our lifetimes. However, everyone’s experience of both bereavement and the grief that goes with it are different. Indeed, each experience for an individual is very different.

Despite these differences, there are some common features. These provide ways to help us understand the grieving process, and deal with it better.

This page discusses some ideas about bereavement and death, to help you cope with your grief, and also to help others who are grieving.

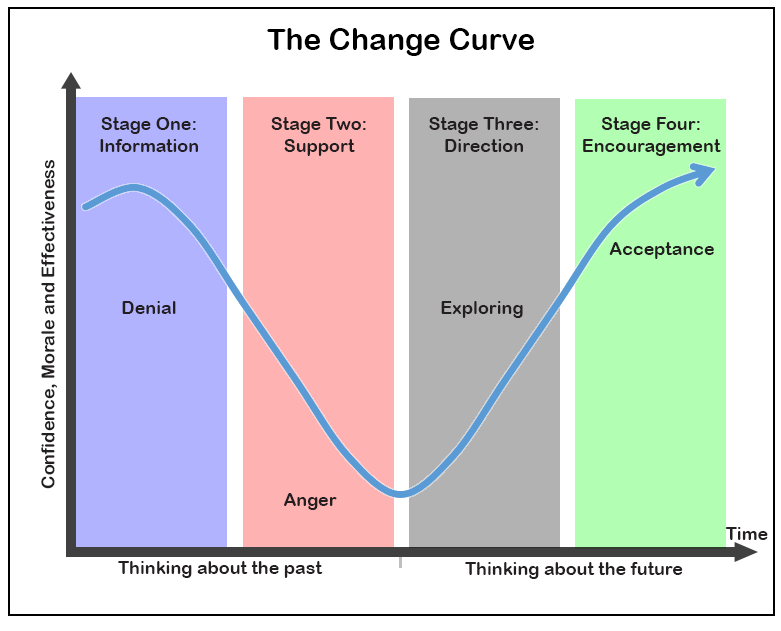

Understanding Grief: The Change Cycle

Our page on Managing Personal Change discusses the ‘change cycle’, a theory about how we manage personal change. This theory is now known to apply to many different kinds of personal change. However, it was originally developed by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross to reflect how people dealt with a diagnosis of terminal illness and being bereaved.

Four Stages of Change

The change cycle describes four stages in moving through grief:

The first stage is denial, the refusal to believe that the death has really happened.

You hear or see this stage manifested in people saying things like:

“I can’t believe he’s not here anymore. I keep thinking I’ll just go into his room, and he’ll be there.”

It is not that they do not KNOW that the other person is dead. They are just finding it hard to adjust.

People may also say things like “I can’t believe this is happening to me. It can’t be real.” This is also a manifestation of denial.

Some people find it extremely hard to move past this stage. You may hear, for example, of people who refuse to move the dead person’s belongings, and keep their room exactly as they left it for many years. Fundamentally, these people are still in denial.

People in this stage are often capable of functioning very effectively, because the reality of their situation has not yet sunk in. However, if it goes on a long time, they may become depressed (there is more information about this in our page on Depression).

The second stage is anger, either at the world or the dead person

You may, for example, hear people saying things like,

“I’m just so angry with her for dying NOW. We were finally going to do [x] this year, and now I can’t.”

“I’m so angry that he’s left me to deal with this!”

“How could he do this to me?”

People in this stage are unlikely to be able to function very effectively. They often lack energy and confidence, and spend a lot of time railing against what is happening.

The third stage is exploration, when people start to think about what this means for them

In bereavement, this stage is likely to be characterised by people discussing their finances, making decisions about where to live, and thinking about how they want to spend their time.

The Right Time for Decisions?

When you look at the change cycle, it becomes clear why it is better to wait for a few months (at least) after bereavement before making any decisions about where you want to live, or what you want to do.

You will be able to make better decisions when you are moving through the exploration phase than when you are either still in denial, or angry.

The fourth and final stage is acceptance, where people start to move forwards again

This phase moves people out of the cycle of personal change, and into a ‘new normal’ for them. They have accepted their bereavement, and can move forwards with the rest of their lives.

This does not mean they are not still grieving, or that they will not feel pain, or that they do not need ongoing support.

However, they have found ways to cope and to move on.

Another way of understanding grief: the Ball in the Box analogy

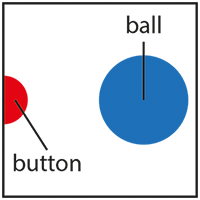

One very good analogy about grief and bereavement is the ball in a box.

Imagine a box. The box has both a ball and a button in it:

The ball moves randomly around the box, and every time it touches the button, it causes you pain.

|

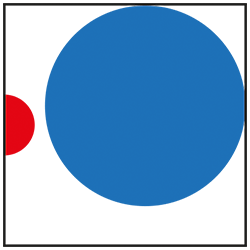

When you are first bereaved, the ball is huge. It fills the whole box.

It is almost impossible for the ball to move without causing you pain. |

|

Over time, however, the ball grows smaller. The ball still moves around the box, and it still hits the button sometimes—and when it does, it hurts. However, it hits the button less often than before. |

|

After a while, the ball gets much smaller. The ball pings around the box, just as it did, and most of the time that’s fine. Sometimes, however, it hits the button. It still hurts as much as ever when that happens, but it doesn’t happen very often. |

Grief and grieving are not logical processes

We have described both the change cycle and the ball in the box as if grieving was a simple, linear process, following an entirely logical course.

In reality, of course, it is not that simple. People rarely move straight from one stage into the next, without any regression. Sometimes they appear to be exploring the future, and then dive straight back into denial and/or anger—and this is especially true if something unexpected happens to them.

There will also be days when the ball seems to have grown much larger again, because it is hitting the pain button so often.

It is therefore best to see these analogies as a sort of guide to overall progress, rather than a clear map of the way.

Supporting Someone who has been Bereaved

There are several ways that you can support someone who has been bereaved. These include:

Providing support and sympathy

People need different levels and types of support when they have been bereaved. Some people need more practical support, and others need more emotional support. However, there is no question that having people there to listen will always be helpful.

Ring Theory: Comfort In, Dump Out

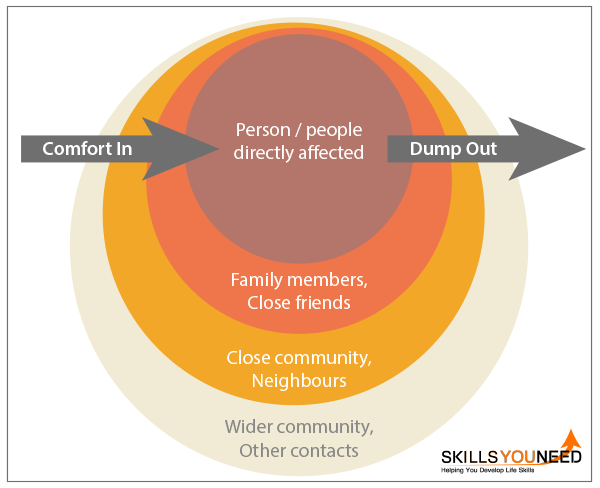

Our page on sympathy describes the idea of ‘ring theory’ to help people respond to traumatic events in their own lives and those of others.

Imagine a series of concentric circles. In the centre circle is the person or people who are most directly affected by the trauma. In the next circle are their direct family and closest friends. Outside them are more distant family and friends, then acquaintances and so on.

The person at the centre of the circle can say what they like to anyone. They can vent at any time, or in any way. Those beyond that, however, can only vent OUTWARDS. Inwards, they need to express sympathy and provide comfort.

The rule is simple: Comfort In, Dump Out—however badly you feel about what has happened.

Sending cards and sharing memories

In Western countries, there is a tradition of sending letters and cards to bereaved people. If you have been bereaved, you will know that this is a bit of a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it is lovely to know that people care, and to read their memories about the person who has died. However, it is also painful to stir up your own memories.

On the whole, the good outweighs the bad, especially over time. Sending a card is a comfort, so please do it, even (perhaps especially) if you are not sure it is your place to do so.

It never hurts to tell someone that you are thinking about them.

Keep being there

Many people report that one of the hardest things about being bereaved is that people stop asking how you are, and stop checking in, after a few days or weeks. They assume that you are now ‘back to normal’.

The best friends carry on being there. They keep inviting you to do things, and phoning to make sure you are coping—or just to give you someone to talk to. They remember about anniversaries and birthdays—always the hardest times—and they make sure that they call then.

Grief lasts for a long time—and it helps when people recognise that.

The Effect of Time

It is helpful to remember that there is no substitute for time in bereavement.

Time doesn’t exactly heal all wounds, because some can never fully heal, and will always leave a scar. However, it does make them easier to manage.