Innovation Skills

See also: Creative Thinking SkillsBeing innovative, or innovating, is a skill like any other.

There are people who appear to fizz with new ideas, throwing them out every other day, or so it seems. We can all develop our innovation skills with a bit of practice.

The skills and techniques of innovative thinking are not just vital in work, but useful in everyday life as well, helping us to grow and develop in new situations and think about how to adapt to change more easily.

What is Innovation?

Defining Innovation

Innovate, v.t. To introduce as something new. Innovation n. the act of innovating.

Chambers English Dictionary, 1989 edition.

The process of bringing any new, problem-solving idea into use… Innovation is the generation, acceptance and implementation of new ideas, processes, products or services.

Kanter, R.M. (1984), The Change Masters: Innovation and Entrepreneurship in the American Corporation, Simon and Schuster, New York, NY.

Innovation is therefore, and crucially, not just the generation of new ideas but being able to put them into useful practice on a daily basis.

Types of Innovation

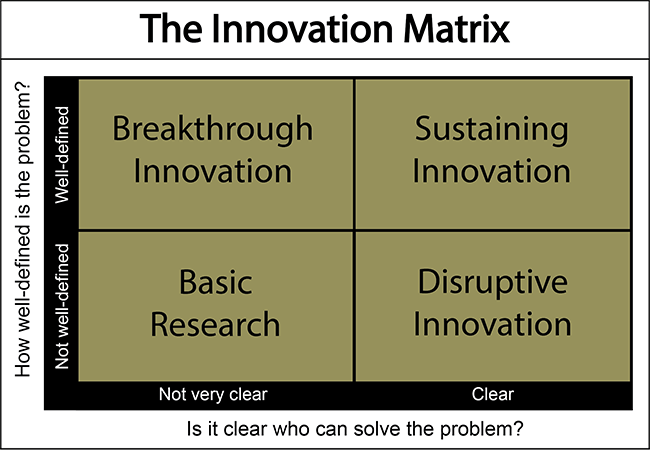

At an organisational level, there are four main categories of innovation, which can be distinguished by whether the problem is well-defined, and whether it is clear who is best placed to solve it.

These categories of innovation are:

Basic research, where there is no clearly defined outcome. The idea is to explore how something works. Many commentators consider that basic research is not innovation because it does not involve the application of the new findings. However, it is an essential precursor to much innovation because it is often only by understanding how things work that new ideas emerge or can be applied.

Sustaining innovation, where the problem is clearly defined, and it is also clear who is best placed to solve it. An example of this type of innovation is the iPod, where Steve Jobs had a clear idea that there was a market for a device that allowed you to ‘put 1000 songs in your pocket’. The nature of the problems was clear, as were the skills needed to address them.

Disruptive innovation, which introduces new approaches to old products or services. A good example of this would be the development of budget airlines, which cut out the expensive parts of the service that people tended not to value and radically cut the cost.

Breakthrough innovation involves a paradigm shift and often, but not always, requires someone from outside to bring a new perspective. An example would be the discovery of the structure of DNA, where Watson and Crick quite literally turned the previous thinking inside-out.

These categories can be mapped onto a matrix:

Environmental Influences on Innovation

Different environments will favour different categories of innovation. For example, basic research is best done in an environment where there is very little pressure to solve particular problems but where the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake is valued, such as a university. Many companies do invest in basic research, however, often by sponsoring placements and students at universities.

Sustaining innovation is the most likely to emerge from an established R&D program in a large company. Big companies can invest in developing new ways of using existing technology, or improving existing technology to make it cheaper or better quality, and would expect to see a reasonable return on such investment.

Disruptive innovation tends to happen where new competitors emerge in an established industry, partly because a new company can think differently. It’s very hard to innovate disruptively deliberately, because it’s often not clear what the problem is that you’re trying to solve. Those companies that have done so successfully tend to have looked at the existing offering, and then very deliberately targeted the areas that it does not meet.

Example

Formule 1 Hotels, in France, looked at their existing hotels beside motorways and noticed that they tended to have large lounge areas which nobody used and big bedrooms which wasted a lot of space, so that they had relatively high costs.

The company reduced this space, fitting in more rooms, and enabling them to offer much cheaper accommodation, which was favoured by customers looking for inexpensive roadside lodgings.

Breakthrough innovation tends to need outsiders because those already working in the area have ‘hit a brick wall’. Established companies will often sponsor innovation prizes to solve particular problems as a way of bringing in this fresh thinking.

The Innovator’s Dilemma: Balancing Sustaining and Disruptive Innovation

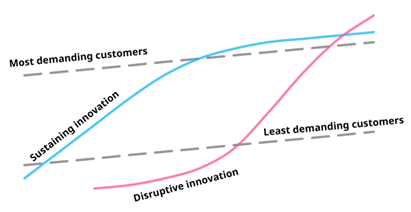

The Innovator’s Dilemma is a phrase coined by Clayton Christensen in 1997.

It describes the problem that in their early days, disruptive innovations are generally less profitable and less attractive to customers, especially more demanding customers, than sustaining innovations. However, over time, some but not all disruptive innovations ‘take off’ and become more attractive, to the point that they overtake the previous products or services (see graph).

Disruptive innovations are therefore much less attractive to the incumbent players in any market, because these companies have more to lose. The problem is that disruptors move into the market, and then get a ‘first mover’ advantage with the disruptive innovation. By the time the incumbents realise that this particular innovation has taken off, it is often too late to catch up.

The Innovation Process

There are plenty of people who argue that innovation has to be a free-flowing process, and that it is impossible to ‘manage’ it within an organisation. However, there are also plenty of organisations that use a structured process to manage innovation successfully.

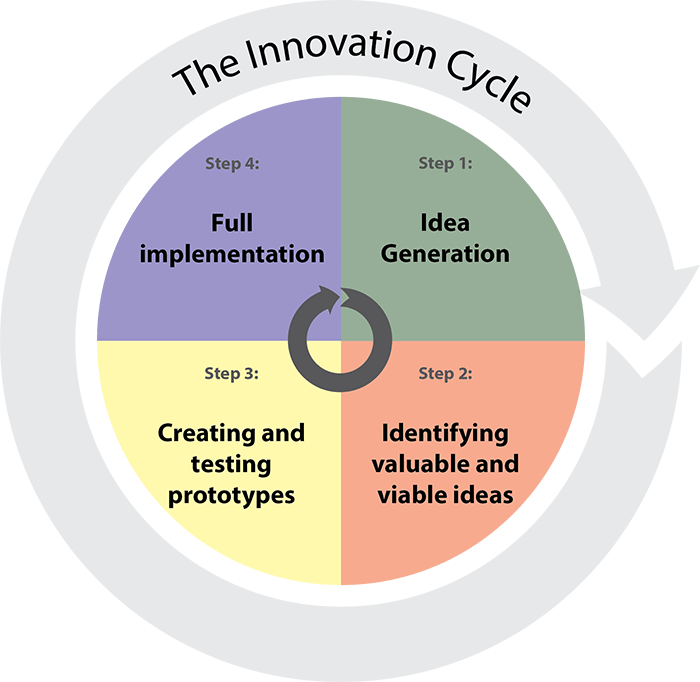

Generally speaking, the innovation process follows a cycle such as the one illustrated in the diagram below. This is a fairly typical cycle, although some organisations may build in extra steps such as an earlier problem identification stage.

Innovation and design thinking

Anyone familiar with the concept of design thinking will probably notice that this cycle is very like the design thinking process. This is because design thinking is an alternative process for managing innovation.

For more, you may like to read our page on Design Thinking.

This cycle has four stages:

Ideation or idea generation

This first stage is the process of generating ideas, where ‘anything goes’. Organisations often use processes like brainstorming for this part of the innovation cycle.

Identifying valuable and viable ideas

During this stage, the flood of ideas from the first stage is narrowed down to identify the most attractive. These are generally those that are attractive to customers, technologically feasible and economically viable (and see our page on Design Thinking for more about bringing these three together).

Creating and testing prototypes

During this stage, the organisation will create and test prototypes that represent particular ideas or parts of ideas. The testing may be both customer-based and feasibility-based.

Full implementation

The final stage is to put the products into production. This is often the most difficult, because what worked well as a prototype may be much harder to mass-produce. There are also several stages to implementation, with scaling up in the marketplace being particularly hard to achieve (see box).

Crossing the Chasm: Challenges in Going Mainstream

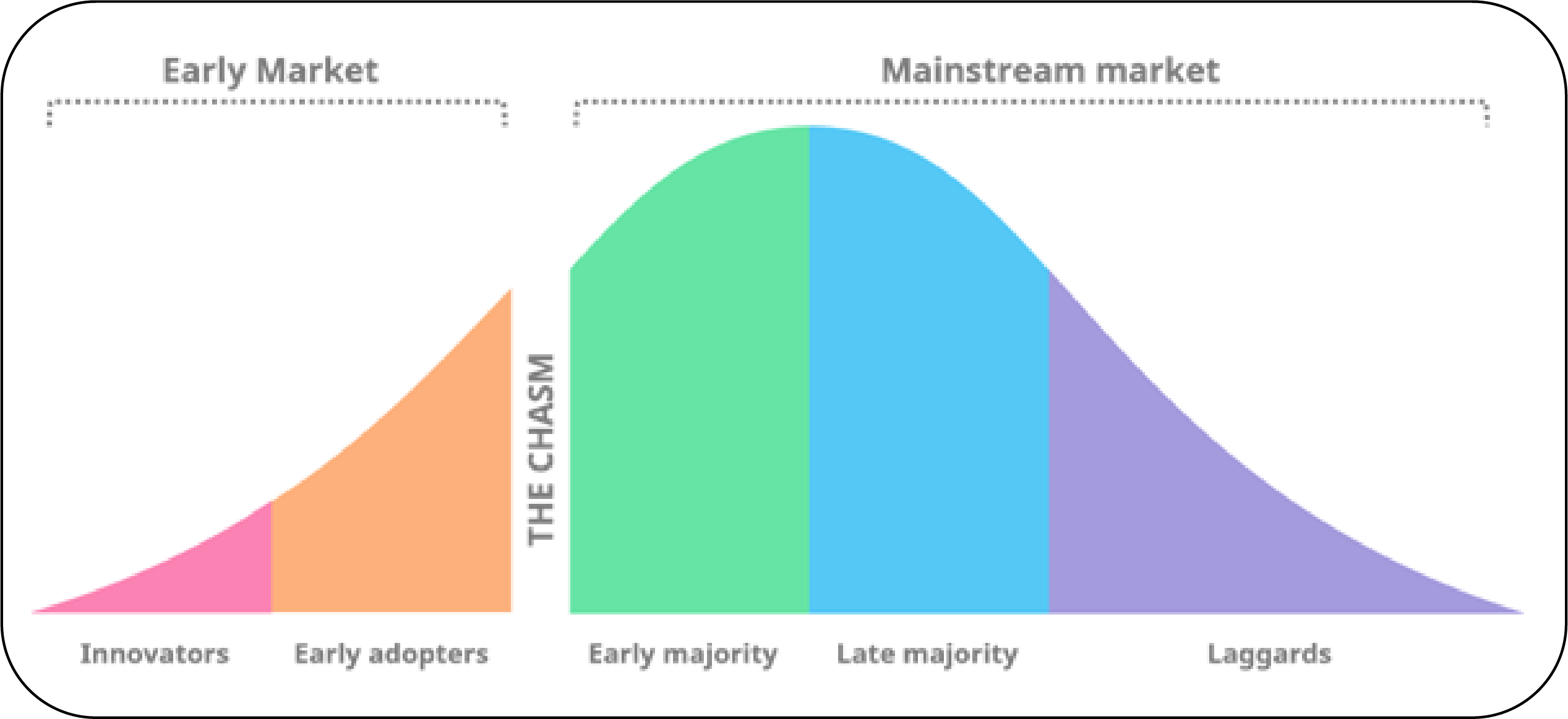

Research on how people adopt innovations shows that you can identify distinct groups by the time at which they start to use new products.

The first people to adopt innovations are other innovators. They often improve the product themselves, or make useful suggestions for improving it.

The next group are the early adopters. They like to be first to have new products, and value their novelty and uniqueness, to the extent that they are often prepared to pay more for these products.

After that, there is a gap, described by Geoffrey Moore in a 1991 book as ‘the chasm’:

This gap is the move from early adopters to mass market adoption. Many products never make that jump, because it requires a change in thinking. To cross this chasm, companies have to find a way to make their products attractive to the early majority. The problem is that this may mean alienating your early adopters—and some companies cannot bear to do that. Unfortunately, the early adopters will probably move onto the next new thing anyway.

Crossing the chasm needs both marketing and product thinking. You may have to change the product: make it simpler, or cheaper, or both. You may also have to market it differently, because you need to show that it is proven to solve a particular problem or issue.

Other Models of Innovation

There are two more models of innovation that may be useful to organisations: the McKinsey Three Horizons of Growth, and the Google 70-20-10 Rule. These two are closely related.

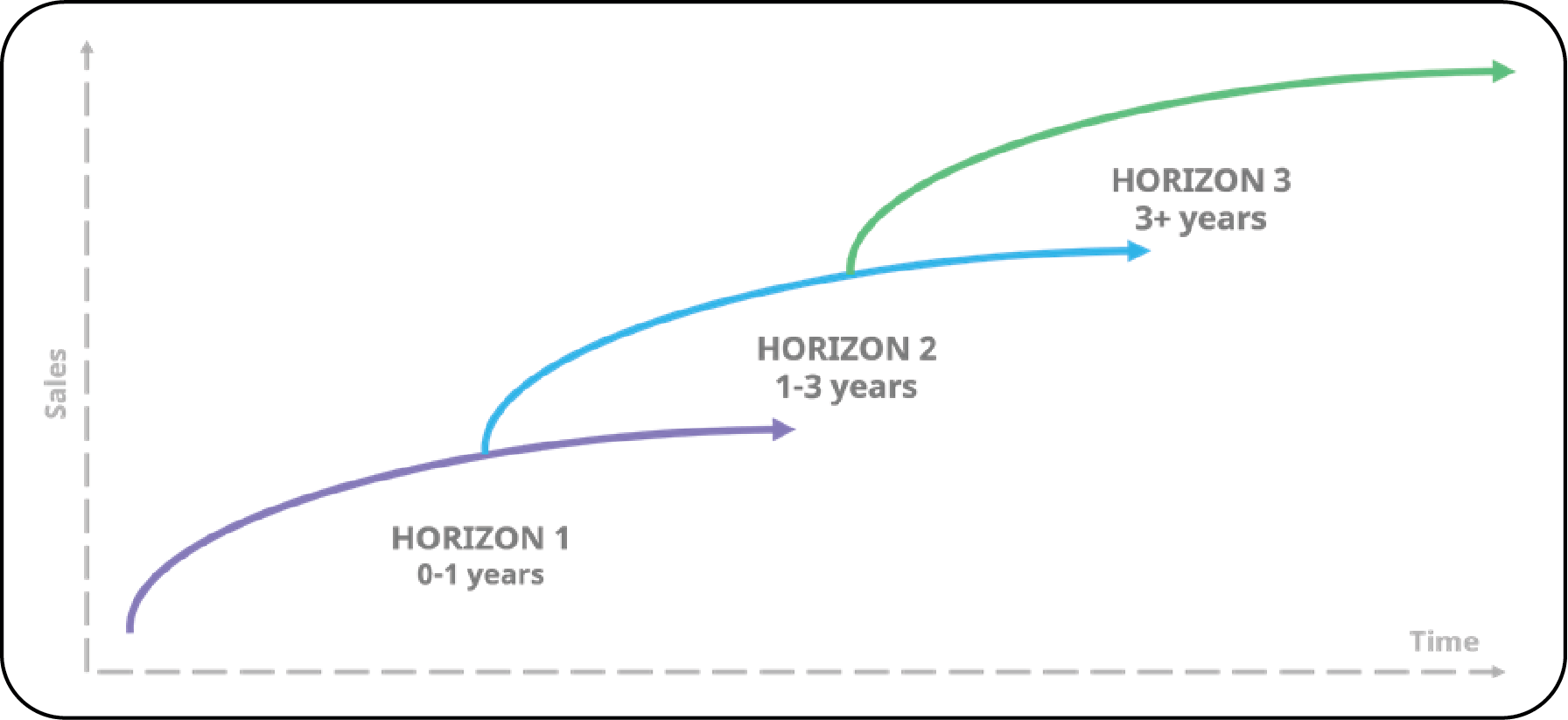

Three Horizons of Growth

This model is designed to help companies think about their balance between short- and long-term projects. The idea is that there are three ‘horizons’ for innovation projects (see diagram).

The first will deliver within a year. The second will deliver from one to three years’ time, and the third will deliver in more than three years. The key is that successful innovation requires projects across all three time horizons. This will balance risk and reward over time.

The 70-20-10 Rule

The 70-20-10 rule is a way of dividing resources between three parts of the business:

The core, or the majority of the company’s existing business;

The adjacent, or logical extensions of your existing business, such as taking existing products into new markets; and

The transformational, or anything that is fundamentally new to the organisation.

Interestingly, research by Google suggests that companies that divide their resources in this way tend to see rewards that are inversely proportional to the investment. In other words, 10% of their returns come from core business, 20% from adjacent business, and 70% from transformational projects.

Not an absolute rule

The 70-20-10 rule should not be considered hard and fast in terms of the precise allocation of resources. It’s a good starting point, but it won’t be right for every organisation.

This rule fits closely with the three horizons. It provides a precise numerical division of input and rewards, rather than simply suggesting a ‘balance’ between them.

Approaches to Managing Innovation and Change

After studying a large number of organisations, Rosabeth Kanter suggested that there were two organisational approaches to innovation and change: integrative and segmentalist.

Integrative organisations treat innovation as an opportunity and not a threat. They tend to deal with problems as a whole organisation, rather than in separate sections, and are enthusiastic about new ideas. Generally, these organisations are more flexible and willing to change.

Segmentalist organisations tend to work in silos, with each bit of the organisation dealing separately with problems relating to change, and management not taking an overall view. Such organisations are generally unwilling to change their structure, or alter the relationships between different bits of the organisation, which makes them very inflexible.

Kanter concluded that integrative organisations handled change and innovation much better. She further suggested that people within integrative organisations showed three key skills that were vital to managing innovation.

Three Key Skills for Innovating

Power Skills:

Being able to persuade others to invest time and money in new and potentially risky initiatives.

See our pages on Persuasion Skills and Risk Management for more.

People Management Skills:

The ability to be able to effectively cope with difficulties arising from team-working and, in particular, individual team members’ participation or non-participation.

See our pages: Working in a Group or Team, Building Group Cohesiveness, and Difficult Group Behaviours. For more general problem management skills, see our Problem Solving section.

Change Management Skills:

To understand how change can be positively designed and ultimately constructed within an organisation.

See our pages on Change Management for more.

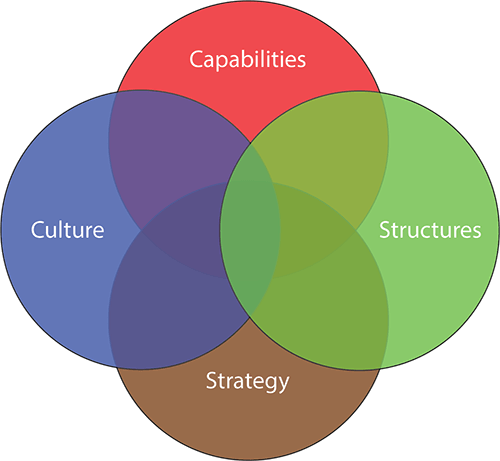

How would an organisation go about becoming more integrative and better at innovation? There are four main areas to consider (see diagram).

Capabilities is the abilities and resources that the organisation has to deliver innovation. These include the skills of the individuals within it—and particularly in the three key areas identified by Rosabeth Kanter.

Structures is the organisational processes, hierarchies and other structures that enable effective use of the organisation’s capabilities. It includes the structures used for innovation: for example, having a separate part of the organisation that is responsible for innovation.

Culture is the ‘feel’ of the organisation, or ‘how we do things around here’. It is what enables the organisation to acquire or develop the capabilities related to people, such as skills. It is also how the capabilities and structures are used in practice.

Strategy is the choice that the organisation makes about where to focus. There is seldom an obvious route to commercial success. The organisational strategy describes the choice that the organisation makes about which route to pick. The key is for innovation to be aligned with strategy. For example, it makes no sense for your strategy to be focusing on consolidating within existing markets if all your innovation is around new products or markets.

Organisations need to consider all four for success. Focusing only on individual skills will not help if the structures and culture of the organisation do not support innovation. Similarly, putting the right structures in place is no help if you do not have the skills to take advantage.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Leadership eBooks

Learn more about the skills you need to be an effective leader.

Our eBooks are ideal for new and experienced leaders and are full of easy-to-follow practical information to help you to develop your leadership skills.

Personal Innovation Skills

Although we often talk about innovation and change as something that is most important for organisations, and for those working within them, the skills necessary for working innovatively are crucial in everyday life.

The approach used by integrative organisations towards innovation, of being flexible and adaptable, and treating change as an opportunity, is a useful approach for an individual too.

The three key skills for innovating: power skills, people management and change management, if developed and strengthened, will help you take a more confident, and therefore more relaxed, approach to new situations. This, in turn, will help you to cope more easily with change.