Understanding Change

See also: Implementing ChangeThis page covers some of the core theories of change. Understanding the nature of change will help you to manage change more effectively - for you and others around you.

Follow the evolution of change management theories, from the engineering perspective of the early years of the twentieth century, through biological and interpretative views in the 1950s and 1980s, to complexity theory in the 1990s.

There is no one right way to manage change, and there are also many perspectives on it. Some will work for some people, or some situations, and others will fit at other times and in different places. The more you can understand change, and how it has been perceived and explained by others, the easier it will be to find your own way of managing it.

Theories of Change

Mechanical or Engineering School

This school of thought emerged in the early years of the twentieth century, from the Western industrial revolution. With that background, it probably makes sense that change was considered in terms of increasing productivity and efficiency. But it’s not a school of thought that can stand alone for long: as soon as you introduce people to the equation, whether employees or customers, this view starts to look a bit limited.

Biological School

In the 1950s, therefore, academics began to draw on biology, and particularly evolutionary theories to explain change. They talked about adapting, re-positioning, alignment and congruence. Evolutionary change theory, however, also has its limitations. Evolution, after all, is not something that an organism, or indeed a population, does consciously. Far from it, in fact. So using evolutionary thinking as a basis for managing large-scale change may be more tricky.

Interpretative School

Instead, academics and practitioners alike started to think in terms of cognitive change. The interpretative school talked about systems that created meaning. An important factor was cultural change. It’s perhaps no coincidence that this school emerged in the 1980s, at a time when huge political and cultural changes were happening around the world. This school emphasised that change processes don’t happen quickly: you need time to build up momentum, and then to embed the change in the organisation.

Complexity School

Towards the end of the twentieth century, the world started to change at a pace faster than had even been seen before, especially in terms of technology. The old methods of managing change, taking five to ten years to embed the change in a new culture, just weren’t enough. Academics began to draw on complexity theory to explain change. Where you don’t have time to organise or manage change in any formal way, the ideas of self-organising systems start to seem very attractive, with their focus on conversation, making connections between individuals, and empowerment.

Why Change Happens

Setting aside the cynical view that everyone likes to leave their mark on an organisation, and the importance of moving the chairs around on the deck of the Titanic.

There are many reasons why change becomes essential to an organisation, often linked to its environment, such as:

-

The political situation, perhaps a new government, or even a new system of government;

-

Economic aspects, for example the state of financial markets, how easy it is to get funding for business expansion, or whether a recession means fewer people are spending money;

-

Social issues, for example in the nature of the workforce, whether it is highly educated, or not;

Technological aspects, like changes in technology that have led to the development of smartphones.

Changes in any or all of these areas can have drastic effects on the profitability of a company or organisation, or even threaten its existence altogether. Organisations may need to change dramatically to survive.

See our page on PESTLE for more on this.

Disruptive Change

Most organisations and individuals are in a constant state of change: minor adaptations to ensure that they cope with the changing demands of each day and week. These changes go largely unnoticed, as they are a normal part of life - they represent evolutionary change. In talking about ‘Understanding Change’, we are considering large-scale, disruptive change.

For an individual, this might be moving to a new city to start a new job.

For an organisation, it might be moving from a product-focused mentality, to developing a service for its customers around the product.

Two academics, Ansoff and McDonnell, developed a model in the early 1990s to link performance to environmental turbulence, covering all four of the aspects mentioned above. They believed that an organisation performed best when its assertiveness and responsiveness matched the level of turbulence in the environment.

Five Levels of Environmental Turbulence

- Predictable

The future is expected to be the same as the past. - Forecastable by extrapolation

The future can be predicted to a certain extent by looking at patterns from the past - Predictable threats and opportunities

Accurate forecasting is possible, but much harder, as the environment is more complex - Partially predictable opportunities

The environment is much more turbulent, and the future is very hard to predict - Unpredictable surprises

Unexpected events occur too rapidly for the organisation to react effectively.

Models of the Process of Change

The Transition Curve

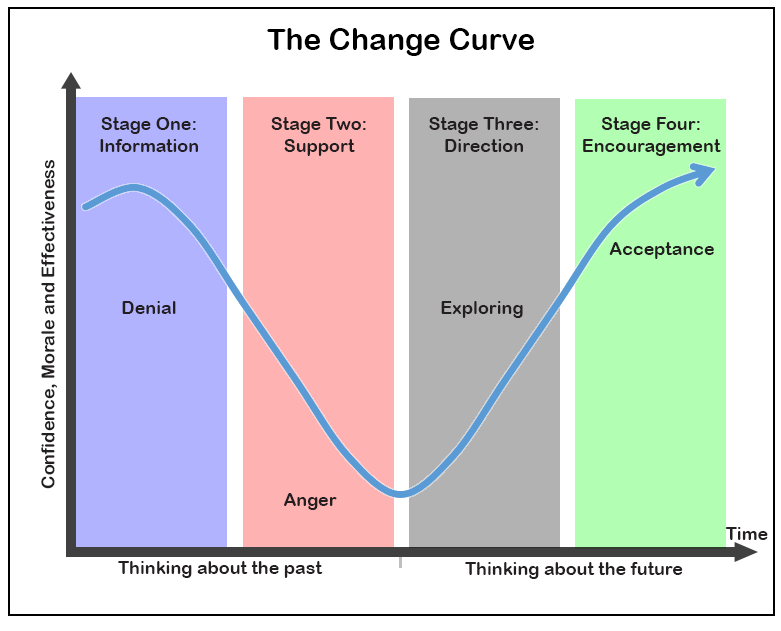

The Transition Curve, or Change Curve, was developed originally by Elizabeth Kubler-Ross to show how people come to terms with having a terminal illness, and is a useful way of thinking about change. It shows the changing levels of confidence, morale and effectiveness within an organisation or individual, as a change process develops, and shows how initial ignorance or denial gives way to anger, then exploration and finally acceptance.

Many organisations and individuals make the mistake of seeing a high level of energy early in a change process, and assuming that they are on the upward curve, and have therefore successfully bypassed anger. It’s much more likely that they are bang in the middle of Phase 1, and most people are either actively in denial, or still in blissful ignorance. Change takes longer than you think.

The Change Cycle

There are many other models of the process of change, such as the ‘change cycle’, or Kotter’s eight step model. Although there are many slight variations, most share a core of:

- Establishing a need for change

- Building leadership for change

- Creating a shared vision or direction

- Implementing the necessary change

- Consolidation

- Sustaining the new culture

Understanding Organisational Culture

Understanding culture, whether organisational or individual, is vital for understanding change. Edgar Schein, an expert on organisational change, described three elements of culture: artefacts, values and beliefs and basic assumptions.

Schein's Elements of Culture

Artefacts are the physical evidence of existence of an organisation, such as people, buildings, or products.

Values and beliefs set out the spoken understanding of what makes the organisation ‘tick’. It is likely to include words like ‘teamwork’, ‘innovation’ or ‘entrepreneurship’.

Basic assumptions encompass all the unspoken elements about what works for the organisation, including basic beliefs about why it has been successful.

Having the wrong ‘basic assumption’ can stop a change process in its tracks.

For example, an organisation that fundamentally believes that it’s a product-making organisation is unlikely to succeed in developing any service aspects until it addresses its basic belief.

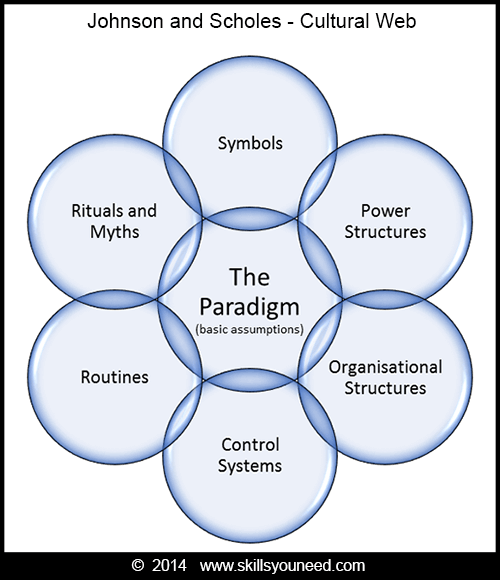

One good way to explore organisational culture is to draw a ‘cultural web’, originally developed by Johnson and Scholes, which looks at various aspects of culture, and how they interact.

At the centre of the web lies the paradigm, or basic assumptions.

Around this spin all the elements of culture:

Routines: how we do things around here

Rituals and myths: the stories that are told, such as who are the villains and heroes, which show what is really important to the organisation

Symbols: the trappings of power, such as logos, car parking spaces, doctors’ white coats

Power structures: where does the power lie in the organisation, including who can stop things happening

Organisational structures: the formal and informal hierarchy

Control systems: such as measurement and rewards systems

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Leadership eBooks

Learn more about the skills you need to be an effective leader.

Our eBooks are ideal for new and experienced leaders and are full of easy-to-follow practical information to help you to develop your leadership skills.

Conclusion

There are many different ways of looking at change and trying to understand it. Among the information on this page, you will hopefully find one or two tools or theories that will help you to make sense of changes happening in your life or organisation.