Complex Carbohydrates, Sugars and Diet

See also: What is Sugar?Our page What are carbohydrates? explains that there are two types, simple and complex carbohydrates. It sets out that simple carbohydrates, also known as sugars, are often found in refined or processed foods. It also suggests we should all be trying to reduce the amount of sugar that we eat, and get more of our energy from more complex and less refined carbohydrates.

However, the picture is more complicated than this summary suggests. Complex carbohydrates such as starches are also broken down into sugars by the body, and therefore often have very similar effects on our bodies. This page explains more about how carbohydrates are metabolised in our bodies—and what we need to know to avoid building up problems for the future.

A Global Picture

The amount of sugar in our diets is rising gently but almost inexorably around the world.

In 2010/11, the total sugar consumption worldwide was 155.8 million metric tonnes. By 2022/23, this had risen to 176.01 million metric tonnes. In those 13 years, annual global consumption has only decreased twice. Indeed, the increase has actually been going on for a much longer period.

One reason for the increase is that, in the 1970s, dietary fat was linked to heart disease, obesity and high blood pressure and so food manufacturers responded by replacing fat with sugar in many products. In addition, evolution has programmed humans to like sugar. This is partly to ensure that we have enough energy in our diet, and partly because fructose, a component of sugar, helps us to store fat, which was an important advantage when food was scarce.

Does the increased consumption of sugar matter? The answer is an emphatic yes. Sugar in our diets has been linked to various health problems, including the so-called obesity epidemic, and various metabolic problems such as insulin resistance, diabetes, heart disease and stroke. It also has a direct impact on the potential for tooth decay. This has implications for each of us as individuals—but it has huge societal implications too.

However, the problem does not relate to sugar alone.

There is growing evidence that it is how we consume carbohydrates of all kinds that matters, and not just our sugar intake.

The Metabolism of Carbohydrates

What happens when we eat carbohydrates?

The exact metabolic pathway depends on which carbohydrate we have eaten. However, in general they are broken down into the constituent monosaccharide units before being absorbed into the body. For example, starch consists of multiple glucose molecules connected together. Sucrose (what we usually call ‘sugar’) is a disaccharide that combines glucose and fructose.

See our page What is Sugar? for more on what we mean by monosaccharides and disaccharides.

Glucose is the primary energy source for most living organisms because it can be broken down to release energy more easily than either fats or amino acids. However, it is difficult for the body to store glucose because it is water-soluble. Glucose is therefore converted to a less soluble polysaccharide called glycogen for storage in muscles and the liver.

Dietary glucose is absorbed directly through the intestinal wall into the bloodstream. Blood glucose levels immediately go up, and this triggers a release of the hormone insulin from the pancreas.

Insulin promotes the absorption of glucose into cells, reducing blood glucose levels again. If energy is required by the cells immediately, glycolysis begins and the glucose is metabolised to release energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).

However in the absence of an energy demand, the glucose is turned into glycogen and stored for later use. When the body needs energy, this glycogen is converted back to glucose. This may be either aerobically, which produces more energy per unit of glycogen and is important for endurance activities such as running, or anaerobically, which produces less energy per unit but is a faster process, for activities such as sprinting.

Fructose (the other monosaccharide in common sugar, or sucrose) has a different metabolic pathway from glucose and cannot be used directly for energy by cells. Instead, fructose is absorbed through the intestinal wall and transported to the liver where it is metabolised using one of two pathways. When either blood glucose or glycogen levels are depleted, fructose is metabolised first into glucose and then into glycogen. If the glycogen stores are full, it is metabolised into triglycerides or fatty acids, which are then stored in adipose tissue.

Galactose is not generally found free in nature in large quantities, but forms part of lactose. It is less sweet than glucose but can be metabolized into glucose and therefore glycogen when necessary.

However, this is not the whole story.

Blood Glucose Levels and Carbohydrates

When you eat carbohydrates of any kind—whether rice, pasta, potatoes or chocolate and other sweets—you (almost) immediately get higher levels of blood glucose. As the insulin kicks in, the spike of glucose is controlled, and the level drops again.

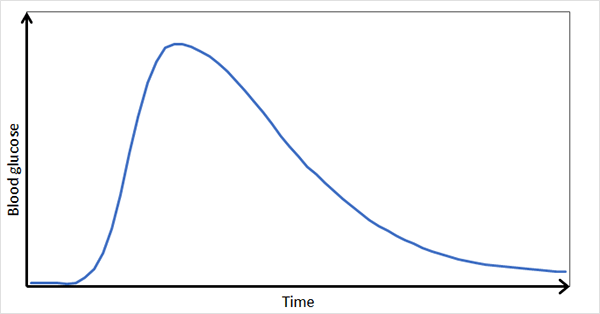

If you were to draw a graph of this, it would look something like this:

This is what we call a blood glucose ‘spike’. When this is high (above about 30 mg/dL), it is bad news for the body.

When we have a spike like this, it harms our cells through a series of stress reactions. Our cells start to produce free radicals, which are destructive to the cells, cause mutations in our DNA, and lead to what is called ‘oxidative stress’. This is generally bad for our bodies.

This process is associated with obesity, heart disease, diabetes and other metabolic problems. Glucose spikes also cause a process called glycation, which is directly linked to aging.

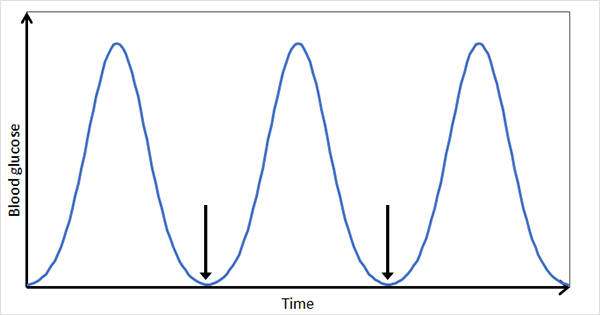

If, therefore, you spend a lot of your day snacking and/or drinking sugary drinks (the downward arrows on the graph below), you can see that your blood glucose fluctuates wildly over time. What’s more, you will find that when your blood sugar drops, you immediately want more sugar, resulting in having another sugary snack or drink, and perpetuating the problem.

You are likely to find that you have headaches, skin problems such as acne, mood swings, hunger, food cravings and a variety of other unpleasant symptoms.

Fortunately, there is an answer.

Instead of allowing these spikes to happen, we should be aiming to keep our blood glucose levels more consistent, or ‘flatten’ the spikes.

How do we know?

Much of the information on this page comes from the work of Jessie Inchauspé, a French biochemist known as the Glucose Goddess on social media. She has done a lot to raise awareness about the effects of eating carbohydrates, drawing on high quality studies and also testing her theories on herself using a continuous glucose monitor. She has turned views on carbohydrate metabolism upside-down, showing that all carbohydrates have a very similar effect on blood glucose, and that the difference lies in how you eat your carbohydrates, and not which ones you eat.

You can find out more from Jessie Inchauspé’s website: https://www.glucosegoddess.com or her book, Glucose Revolution: the Life-Changing Power of Balancing Your Blood Sugar.

Flattening the Spikes: Seven Tips

Jessie Inchauspé suggests that there are seven ‘hacks’ that you can use to flatten your blood glucose spikes. These are:

Eat in the right order

Start with vegetables, and NOT carbohydrates. This seems to create a network of fibre in your digestive system that slows down the absorption of sugars and flattens the spike.

Add vegetables to every meal

It has long been a mystery why the so-called Mediterranean diet was so healthy—even though it involved lots of fat and carbohydrates. It now seems that the answer may be that it includes lots of fresh vegetables. Consider adding a salad, or a few more pieces of broccoli, to every meal.

Have a savoury breakfast

After years of vilification, it turns out that some variation of the ‘full English’ breakfast could well be your best bet for the start of the day. Certainly, it seems that avoiding carbs at breakfast time, and replacing them with an egg or some bacon is likely to reduce glucose spikes during the day. If you can’t face that, consider some full-fat yoghurt with nuts and seeds instead.

Only eat fruit whole

This means avoid all smoothies and juice—and absolutely do not believe the claims that smoothies are equivalent to one or more of your ‘five a day’. They are not. When you liquidise fruit, you lose all the fibre that slows down the absorption of the sugars. The sugars become rapidly accessible—and you get a glucose spike.

Choose dessert rather than a sweet snack

This one may be counter-intuitive, but the same food can have very different effects eaten at different times. If you eat something sweet after a main course, it will not give you a sugar spike in the same way that it will if you eat it alone. If you really can’t resist that cake or chocolate bar, at least wait until after your next meal—and eat some salad first.

Start drinking vinegar before meals

Lord Byron is rumoured to have used vinegar as part of a weight-loss diet—and it turns out that there is some science behind this. Drinking a tablespoon of vinegar diluted in water before a meal seems to alter your glucose absorption. The science is available from the Glucose Goddess website if you want to read it.

Take exercise immediately after eating

Your muscles are really good at using up stray glucose, and preventing the blood glucose spike. Instead of flopping into a chair for half an hour after lunch, you are much better going for a ten-minute walk round the block.

Dress up your carbohydrates

You can alter your carbohydrate metabolism by adding things to your carbohydrates (even beyond vegetables). For example, put some butter on your bread, add a couple of spoonfuls of full-fat yoghurt to your bowl of fruit, or eat some cheese with your apple. All these will flatten the spike.

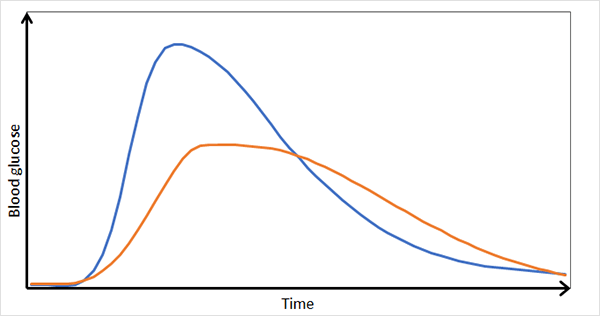

The effect of all of these ‘hacks’ will be to change the glucose spike, to something like the orange line in the graph below (the blue is the original).

The Benefits of Flattening the Spikes

There are many benefits reported from ‘flattening the spikes’ in your blood glucose. These include:

Feeling less hungry, and having fewer food cravings—and in turn, often a link to weight loss.

Feeling more energetic, and sleeping better.

Strengthening your immune system (some studies have reported milder symptoms of COVID-19 in people with better blood glucose control).

For women, less likelihood of gestational diabetes, fewer and less severe symptoms of menopause, and fewer and less severe symptoms of polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Fewer migraines (it seems that migraines can be associated with insulin resistance).

Better cognitive function (brain power), and less risk of dementia and cognitive decline.

Clearer skin, with fewer spots, and a direct impact on acne.

Slower aging, and the development of fewer wrinkles.

Better mental and physical health, including lower risk of cancer, lower risk of heart problems, and remission of Type 2 diabetes.

Sugar and Addiction

Sugar causes a release of the neurotransmitter, dopamine in the brain in a similar way to drugs such as cocaine, heroin and alcohol.

Studies at Princeton University have shown that laboratory rats fed sugar have exhibited all the classical components of addiction such as bingeing, craving, withdrawal and cross sensitization. The same experiments have obviously not been carried out in humans, but many of us would probably report similar experiences.

It seems likely that it is possible to build up a dependency on sugar, resulting in needing more and more sugar to get the same good feeling. For example, many people start off taking half a teaspoon of sugar in their coffee but this may increase to two or more spoons over time. People also report sugar withdrawal symptoms, including headaches, nausea, mood swings, a lack of concentration and the shakes. These generally only last for a short while and can be lessened by slowly reducing your sugar intake rather than cutting out all sugar at once.

Sugar: A Pure White Deadly Poison?

In 2009 Robert Lustig, a leading expert in childhood obesity at the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine, gave a lecture entitled “Sugar: The Bitter Truth” in which he claims that sugar, irrespective of the calories, is a poison in its own right.

Although his view may seem extreme, there is much evidence that supports the argument and promotes the idea that moderation may well be the best approach to our sugar intake.

Unfortunately, our dependence on processed foods and drinks makes this difficult to achieve but it is still an effort worth making.

Giving Up Sugar

In 2002, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommended that sugar should account for no more than 10% of the dietary calorie requirement, which works out to be around 50g per day for a person of average weight. The most recent guidelines in 2014 revised this to recommend that sugar should make up less than 10% of total calorie intake, with 5% being the target.

It is not always easy to reduce the amount of sugar in your diet because of the amount of hidden sugar in many foodstuffs. Some tips to help are:

Read labels – avoid foods with sugar in the first few ingredients, and look out for anything ending in an –ose, or mention of syrups, honey, fruit juice concentrates, or maltodextrin.

Start preparing food yourself. Processed food of any sort, even savoury foods, will contain sugar.

-

Eat fruit whole. You don’t need to avoid fruit, because it is an excellent source of vitamins and fibre. However, it is certainly better to avoid smoothies and juice.

Avoid buying ready-made cakes and biscuits. This will help you to resist cravings. If you want to make your own as an occasional treat, this is fine. At least you will not be consuming ultra-processed food—but don’t overdo it.

Avoid or reduce your alcohol intake. Alcoholic drinks contain high levels of sugar.

In Summary

What we know about carbohydrate metabolism has changed a lot over the last few years. First, we have discovered that it is highly individual, and that our gut microbiomes play an important part in how we manage all kinds of different foods. However, we also know that what really matters is not so much what carbohydrates we eat, as how we eat them, and particularly what we add to them.

If there is just one single message to take away, it is that flattening glucose spikes is relatively simple, but has surprisingly large beneficial effects.