Developing Resilience

See also: Developing and Improving ToleranceResilience is the ‘rubber ball’ factor: the ability to bounce back in the event of adversity.

Put simply, resilience is the ability to cope with and rise to the inevitable challenges, problems and set-backs you meet in the course of your life, and come back stronger from them.

Resilience relies on different skills and draws on various sources of help, including rational thinking skills, physical and mental health, and your relationships with those around you.

Resilience is not necessarily about overcoming huge challenges; each of us faces plenty of challenges on a daily basis for which we must draw on our reserves of resilience.

Four Ingredients of Resilience

There are four basic ingredients to resilience:

- Awareness – noticing what is going on around you and inside your head;

- Thinking – being able to interpret the events that are going on in a rational way;

- Reaching out – how we call upon others to help us meet the challenges that we face, because resilience is also about knowing when to ask for help; and

- Fitness – our mental and physical ability to cope with the challenges without becoming ill.

The Link Between Thought and Emotion

Our page on Recognising and Managing Emotions talks about the importance of applying reason to emotion to support your decision-making. But how you think can be affected by your emotional response to the situation, and part of being aware is understanding this and recognising it when it happens.

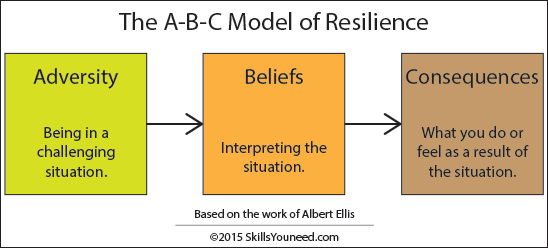

Psychologist Albert Ellis created a simple model for this, which he called A-B-C for Adversity – Beliefs – Consequences. This model sets out a process:

As our page on Managing Emotions makes clear, sometimes an emotion is so visceral that there is no time to go through this process rationally: you simply react immediately to the situation by running away, screaming, or similar. But your brain has almost certainly gone through the process subconsciously.

It is also important to recognise that certain thoughts lead to certain emotions.

| Example Include: | |

| I've lost something | Sadness |

| Someone has done something to harm me | Anger |

| I've hurt somebody | Shame |

| I feel threatened by something | Fear |

The benefit of understanding that these thoughts lead to these particular emotions is that by identifying the emotion we feel, we can understand what our subconscious thought processes may be. This may not be obvious otherwise, and it will help us to take the right action to address the problem.

Thinking Traps

So-called ‘thinking traps’ are traps into which we can fall in our thinking, usually at the ‘B’ stage of the A-B-C model above.

Thinking traps are effectively assumptions about ourselves or the situation, made without examining the evidence, and are usually unhelpful. The signs that you are falling into one of the thinking traps include the use of phrases like ‘never’, ‘always’, and ‘I…they…’, for example:

- “I just can’t do maths”

- “I’ve never been able to do things like that”

- “They’ve taken it away from me”

If you’re thinking that this language sounds very childish, you’re right. Take a look at our page on Transactional Analysis to understand more.

You need to be alert to falling into one or more of these thinking traps when you are developing your beliefs about a situation because it could prevent you from acting effectively: in other words, thinking traps can prevent you from acting with resilience.

Improving Resilience Through Thinking

Having considered the elements of resilience, and the process of responding to situations, it may now be helpful to talk about what we can do to help develop resilience.

There are quite a number of useful techniques here, including:

1. Gathering More Information

You want to engage the rational part of your brain in your decision-making about the situation.

One of the best ways to do so is to actively gather more information on which to base your decision. (See our pages on Decision Making for more general tips and advice).

Example

Suppose that you see a snake by the side of the path. Your immediate reaction might be fear:

“A snake! It must be poisonous! I’d better run away!” [A-B-C]

But pause for a moment and gather more information. It might be dead. It might not be poisonous. It might be cold, and therefore only capable of moving very slowly.

There are all kinds of reasons why you might not need to run away.

A crucial aspect of gathering more information is to think about alternative explanations for the situation.

Your brain, based on your experience and your belief system, will present you with what it considers to be the most obvious explanation.

But it may not be correct!

Thinking about alternatives, and then checking those against reality, perhaps by asking questions of others or looking something up, will help to ensure that you react appropriately to the situation.

2. Alternative Scenarios

We’re all prone to imagining the worst.

Your boss asks to speak to you, and you immediately imagine that you’re about to be fired. You get ready to defend your recent performance…

…but when you enter her office, it turns out that she wants you to know that she’s pregnant and you’re in line to take over her responsibilities while she’s on maternity leave, with a consequent pay rise.

Your child’s teacher asks for a quick word after school. You immediately assume that the child is in trouble …

…but no, they just fell and cut a knee at lunchtime. No harm done, but the school has to let you know.

Imagining the worst is also called catastrophizing, and it is surprisingly common.

There is a very easy way to deal with it, which involves generating alternative scenarios in your head:

Imagine the worst – let your imagination run riot. What could have gone wrong? What might have happened?

Now think about the best possible outcomes. How good could it get?

Finally, think about the most likely outcomes – probably somewhere between the two. Make a plan for how you will respond to that.

These two strategies, gathering more information and looking for alternative scenarios, will help you to develop your resilience.

You will become more aware of what is going on around you, and inside your head (awareness). They will also help you to apply rational thinking to the situation, climbing out of any thinking traps into which you have fallen, and understanding and rationalising your emotional response to a situation.

Improving Resilience Through Reaching Out

No man is an island, entire of itself. Every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main…

John Donne (English Poet)

There is no shame in asking for help. We all need help now and again, and many of us function much better when we are working with others.

A good part of resilience is knowing when and how to ask others for help, reaching out to those with whom we have relationships to resolve the problems with support.

Take a look at our page on Transactional Analysis to explore how you can ask for help as an adult, rather than feeling that you are returning to ‘child’ status by doing so.

Improving Fitness and Health

The final element of resilience is physical and mental health.

Have a look at our other personal skills pages to explore more about how you can improve your health, for example, by understanding the links between diet and stress, and recognising the importance of sleep and exercise

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Life: Living Well, Living Ethically

Looking after your physical and mental health is important. It is, however, not enough. Maslow’s famous hierarchy of needs suggests that most of us need more than that. We need to know that we are living our ‘best life’: that we are doing all we can to lead a ‘good life’ that we will not regret later on.

Based on some of our most popular content, this eBook will help you to live that life. It explains about the concepts of living well and ‘goodness’, together with how to develop your own ‘moral compass’.

Conclusion

Resilience is a multi-faceted capability.

To face challenges and respond appropriately can require us to draw on all our resources, both internal and external, including our personal relationships.

The good news is that improving our resources can help to develop resilience, and there are many ways in which we can do that.