Ethical Food Consumption

See also: A Framework For Learning To Live WellThe ethics of food consumption is a fraught and highly emotional issue. Veganism, vegetarianism and buying organic produce are basically lifestyle choices, but somehow, they have become far more for many people. They are often used as a campaigning platform, a stick to beat those who continue to eat meat or buy cheaper non-organic goods, or even a general signal of virtue.

However, is sustainable and ethical food consumption really just a matter of avoiding animal products or buying organic goods? Are there varying degrees of sustainability within each choice? This page aims to unpick some of the myths and explain more about the choices available.

What is ‘Ethical’ Food Consumption?

What exactly do we mean by ‘ethical’ food consumption?

As with ethical consumption more generally, there are two main issues to consider:

Ethical production

This covers the way that your food is produced.

For example, do your meat, eggs and dairy products come from farms that are following agreed standards of animal welfare? Can you track your food back to its source? Are you buying Fair Trade goods to ensure that producers in developing countries receive a ‘fair’ wage for their work?

There are a huge number of questions here, and the answers are not necessarily black and white.

For example:

Is use of fertiliser good or bad? It is good because it means that farmers can produce more food from the same acreage, so feeding more people with less. However, it is bad if it pollutes water courses.

Are genetically-modified crops good or bad? They are surely good if they enable farmers to produce more food with fewer pesticides and herbicides, but what if the modified genes get into other plants?

These questions, and many others, can only be answered by debate and discussion that draws on scientific evidence. However, we must also recognise that individual ‘red lines’ may be drawn in different places: there are no ‘right answers’.

Organic food: guaranteed ethical production

The label ‘organic’ is defined by law in most countries and jurisdictions. It guarantees certain standards of production, including:

- No herbicides (weedkillers) and limited use of pesticides;

- No use of preventive antibiotics;

- Defined standards of animal welfare, including things like size of herds or flocks and access to outside space;

- No artificial fertilisers; and

- No genetically modified feeds or crops.

The purpose of these standards is to ensure that organic farming is sustainable. You can therefore be confident when you buy organic food that you are consuming food that has been produced ethically.

There is more about this in our page on Organic Food.

However, you have to balance the sustainability against the higher cost of these products. You also have to recognise that organic farming takes more space—and therefore feeds fewer people for each acre of land used. By buying organic, you may therefore be using more than your fair share of resources.

Fair consumption

The issue of fair consumption rests on the idea that we should only consume our ‘fair share’ of the world’s resources.

This means being aware of the ‘cost’ (that is, to the planet and the community) of producing food, and if necessary, reducing our consumption of certain products to avoid excessive consumption.

For more about this, see our page on Ethical Consumption.

Food Choices: Some Definitions

There are a number of terms used in ethical food consumption. For the purposes of this page, we are using the following definitions:

| Vegetarian | Someone who has removed meat from their diet, but continues to consume a range of animal-based products such as eggs, milk and other dairy products. |

| Vegan | Someone who consumes no animal-based products at all, either in food or otherwise (such as leather). |

| Pescatarian | Someone who eats fish but not meat. |

| Plant-based | An alternative term for a vegan diet. |

| Fruitarian | Someone who eats only fruits, nuts and seeds (often defined as products that the plant can give up without dying). |

| No red meat | Someone who eats no red meat (that is, no pork, lamb or beef). The only meat they consume is white meat such as chicken. |

All these are absolutes. However, plenty of people have chosen to reduce but not eliminate their consumption of meat or red meat, or eat a ‘more plant-based’ diet.

The Arguments Against Meat

There are a number of reasons why people choose to move towards veganism or vegetarianism.

The first, and perhaps most obvious, is the ‘cruelty to animals’ argument.

Its proponents argue that by eating animals, we are exploiting them. The conditions in which they are kept are also cruel and unnatural. This argument certainly has some elements of truth: the conditions in which battery chickens are kept, for example, are widely agreed to be very unpleasant.

However, this seems more like an argument for improving farming conditions, and less like one for avoiding animal products altogether.

An argument carried to its logical conclusion

The main argument of many vegetarians and animal rights campaigners sometimes seems to rest on the (heavily paraphrased and slightly exaggerated) idea that “We love these animals. We don’t want to eat them, we want to see them skipping about on the hillsides.”

This argument simply does not stack up.

If we did not eat meat or consume eggs and dairy products, farmers would not rear animals. They are running a business and need to make a living. There would be no (or very few) animals to be seen.

The second argument is the environmental cost of rearing animals for meat.

Agriculture inevitably contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. However, animal farming makes a higher contribution than growing crops.

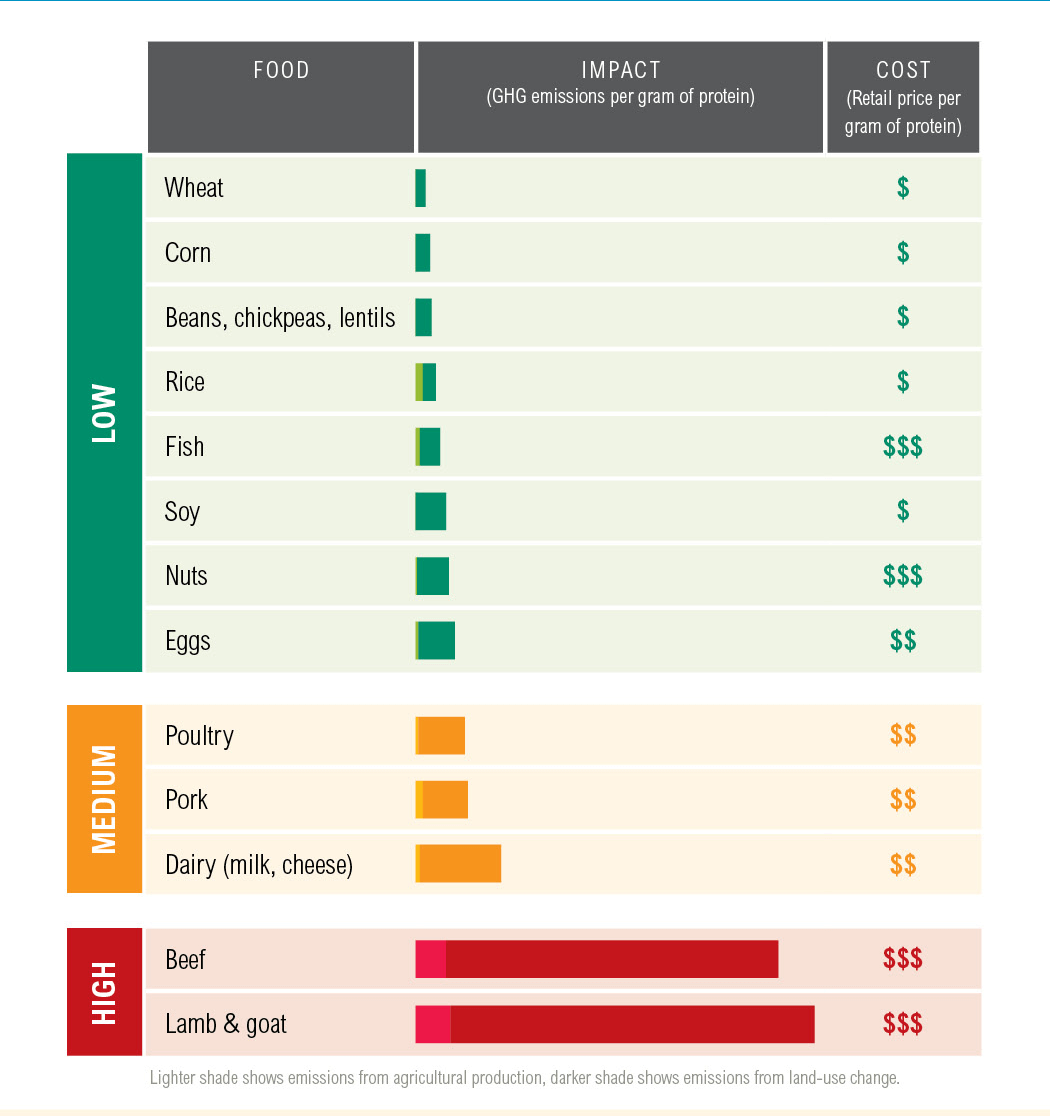

This means that different sources of protein have a different environmental impact. The graph below shows this, and makes particularly clear that producing red meat (beef and lamb) has a much greater environmental impact than poultry, and considerably more than vegetable-based sources of protein.

Source: World Resources Institute.

The graph also shows that some forms of protein may produce relatively few greenhouse gas emissions, but are relatively expensive to produce: fish and nuts, for example. There may also be other issues associated with their production (see box).

Fish, Farming and Fishing

There is now widespread concern about the levels of marine fish stocks around the world. Widespread fishing has resulted in far lower catches, of smaller fish, than at any time in the past.

There is also concern about fishing methods, including the practice of deep-sea trawling, the practice of throwing away fish that are not permitted to be caught, even though they are already dead, to avoid fines, and the danger to other animals of the use of certain nets.

Some sources have suggested that farmed fish may be more sustainable. However, you also need to ask what your farmed fish are eating: for example, it takes 1.3kg of other fish products (in the form of fish food) to produce 1kg of farmed salmon. Nothing is simple…

If you want to find out more about the ethics of salmon farming, you may want to read this article from The Independent, written by two academics from the University of Stirling.

But what about other animal products, such as leather? Leather is, effectively, a by-product of the meat industry, albeit with some additional tanning. Vegans argue that leather should not be worn or used in shoes, because of the animal cruelty involved. Other issues include the potential harm to workers from some of the chemicals used in tanning, and the problem of pollution in developing countries when those chemicals are simply dumped after use.

This might lead you to assume that leather is a ‘no-no’ then. However, ‘vegan leather’ (which is actually a complete contradiction in terms because ‘leather’ is defined as tanned animal skin) also has its problems. Faux leather is, in fact, plastic, and most of us are now aware of the problems that use of plastics can cause.

Some ethical fashion brands are therefore choosing to use ‘best practice leather’, rather than ‘vegan leather’: that is, leather that has been produced from animals kept under ethical conditions and using natural tanning agents. This, they suggest, is actually the most sustainable option.

A More Nuanced Picture?

There is, therefore, more to environmentally friendly food and food product consumption than meets the eye.

The picture is distinctly more nuanced than many vegetarian and vegan campaigners would have you believe.

There is no question that switching to more plant-based sources of protein, at least for some of your meals each week, will produce fewer greenhouse gases. However, it may also have other effects that are not yet clear. Equally, there is no question that organic food is produced in a more sustainable way. However, it also uses more land, and may therefore mean that those who buy organic produce are using more than their fair share of the planet’s resources.

It behoves all of us to ask difficult questions—and properly explore the answers—about how our food is produced. We all need to weigh up choices, and there are no easy answers.