Coaching Skills

See also: Developing Your Coaching PhilosophyWhat are the essential skills that a good coach needs?

Whether you’re a professional coach, a leader or manager using a coaching approach to help your team members develop, or using your coaching skills in a less-formal environment, there are a number of key skills that will help you to become a great coach.

The most important attribute of any coach is that they want to help the person or people they are coaching to learn. A good coach doesn't see themselves as an expert able to fix all problems and having all the answers. Instead, they see themselves as supporting the process of learning.

Our introductory page: What is Coaching? explores the term 'coaching' in more detail and examines some of the differences between coaching, mentoring, counselling and teaching.

Internal vs External Coaching

There are two main types of coaching relationship. The first is with an external coach who is not part of the organisation or line management structure in any way. The second is an internal coaching relationship, where a manager or leader acts as a coach for their team.

The two require different ways of working as coach, although they share some similarities.

In an external relationship, the coach has no subject expertise and no vested interest in the outcome of any decisions, except insofar as the person being coached is pleased with the outcome of the coaching. They also have no preconceived ideas about the person being coached: they probably don’t know them in a work context and have no idea of the quality of their work performance.

In an internal relationship, however, the coach may well have a strong vested interest in the quality of the decision-making, as well as knowing a lot about the subject. They may well know the person being coached very well: they may have been managing them for some time and have some preconceived ideas of the likely outcomes of coaching, which may not necessarily be positive.

The internal coach, therefore, has to work on several issues that the external coach does not encounter:

Putting aside any preconceived ideas about the person and their effectiveness. Try to focus on the coaching process, and what you learn about the individual through that.

Parking your own subject expertise, and helping the individual to develop their own solutions. One good way is to make an effort never to offer a comment, but only ever to ask open questions (so not ‘Have you thought about doing x?).

Not leaping to solutions but, instead, allowing the person being coached time to explore the problem in their own way. Again, continuing to ask questions about the nature of the problem, or what might be a possible solution, is a good way to do this.

Being aware of assumptions made, whether about the person, the process or the subject. See our page: The Ladder of Inference to help you recognise and avoid some of the pitfalls.

Intention and Meaning

We mentioned the danger of making assumptions, but one particularly key area of communication, especially for coaching, is the way that you say something. This often determines whether the immediate response is hostile or receptive.

However, the meaning, or intention, behind your words is also important.

Consider some examples:

| What was said | What was meant |

| You won’t mind if I leave early, will you? | I’m going to leave early even if it’s inconvenient to you |

| Would you mind if I left a bit early? | I’d really like to leave early, but I won’t if it’s inconvenient |

| Shall I drive? | I’d like to drive |

| Do you want to drive or shall I? | I am entirely open to suggestion on who is going to drive |

| Will you drive? | I don’t really want to drive |

It’s not just your intended meaning, either, but also what someone hears as your intended meaning.

For example, if you say “I’d like to leave a bit early today, is that OK with you?”, you may be genuinely concerned that it might not be convenient for your colleague.

However, your colleague may hear “I’m going to leave whether that’s OK with you or not, and you’ll just have to stay here until late if necessary”.

It might, therefore, have been better to have said “I’d really like to leave early today, but I won’t if you need to leave too. If you’re OK with me going early, can I repay the favour another day and you can have an early evening then?”

Why is this difference important in coaching?

Coaching is all about a supportive, permissive relationship. The coach does not tell, but seeks permission to make suggestions and ask questions, respecting the person being coached.

There is a world of difference between saying:

I’ve found that a coaching session often works best if we’re off-site, so would you be OK with going to a café?

and

We’re going to meet off-site, because that always works better.

The first gives the person being coached an option to say no.

The second says “I know what’s best, so just do it”. It does not show respect to the opinion of the person being coached and is unlikely to lead to a productive coaching relationship.

Other Key Coaching Skills and Attributes

Great coaches tend to have a number of key skills and attributes.

Coaches generally have high emotional intelligence: they’re good at understanding and relating to people, and they’re interested in people. You have to genuinely want to help others develop to become a really good coach. It’s no good just paying lip service to the idea.

Coaches need to be able to show empathy and be good at building relationships, including building rapport.

Good coaches also have strong communication skills. For more about developing communication skills in general, see our pages: Communication Skills, and Developing Effective Communication Skills.

Coaching Conversations - How to Say the Unsayable

There will be times in any coaching relationship when you as the coach may feel you need to say something that the person being coached may not want to hear. Whether you say it at that moment—and how you say it—will depend on your relationship with the person you are coaching.

You may consider that if you are led by them, you will not be able to say it.

However, if you consider yourself to be led by their needs and goals, this may open up an opportunity to have the conversation in a different way.

As with any opportunity to give feedback, it is all about choosing the right moment, and the right words.

Coaches are good at gathering information and then clarifying it for the person being coached. They generally have strong listening skills, including active listening.

They don’t jump in straight away with the answer but rather make sure that they’ve fully understood the issue by reflecting and clarifying.

Similarly, coaches have usually taken time to develop strong questioning skills. It’s been said that coaches should never offer opinions, but instead only ask questions to guide the person being coached through the issue. This is similar to the role of a counsellor.

Coaches and coaching leaders give space and time for people to try things out. They don’t get over-excited or angry about mistakes, instead they concentrate on how to recover the situation calmly and with the involvement of the person who made the mistake. They are skilled at providing feedback and using tact and diplomacy.

Coaches may also use various models of learning and thinking, such as Myers-Briggs Type Indicators, and have training and expertise in various tools and techniques, for example, psychometric testing or neuro-linguistic programming (NLP).

A Model of Coaching

Should you have a structure to your coaching, or should you simply be led by the person being coached?

Some coaches find it useful to have a model for their coaching. They find this helps them to structure their coaching around the person being coached and ensure that the coaching is as effective as possible for that person.

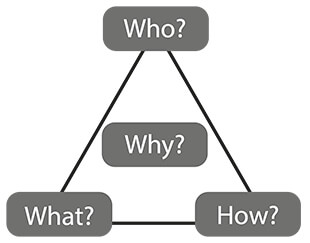

One useful model of coaching is the triangle model (see diagram).

Before starting any coaching session, a good coach should consider each of the three questions around the outsider of the triangle in relation to the person being coached:

Who is the person that you are coaching today?

Consider their goals for the coaching, both today and in general. Also consider their mood today: it is no good trying to have a coaching session on a pre-agreed topic if they are seething about something else that happened this morning. You have to tailor the session to fit the person on the day.

What is your focus for the coaching session?

What will your session cover? You cannot cover everything in every session, so what are you going to consider today? This should ideally be led by the person being coached, but it can also help for coaches to consider what they think the focus should be. After all, we do not always know what we don’t know, and sometimes learning needs a bit of a steer!

How are you going to address it?

This is particularly pertinent for sports coaches, who may do very different activities in different circumstances. However, it is advisable for all coaches to consider. You may, for example, want the other person to complete a psychometric test, or to discuss the results of a previous test. They may have flagged up a problem, and you need to consider how best to respond to it.

At the centre of the triangle is the most important question: Why?

Some people place the coach at the centre, and some the person being coached. However, it seems most appropriate to put the question ‘Why?’ there, because it addresses both other options. This question is:

Why are you doing this?

Why are you coaching this person, and why do they want to be coached? What do you and they hope to achieve as a result?

This question is probably best considered in the long-term, rather than for this particular coaching session. However, you need to bear it in mind whenever you are answering the other three questions about the session.

Coaching Assessment

How can you as a coach help the person you are coaching to identify what to focus on?

The model of coaching suggests that they are in charge—but the Model of Conscious Competence (and see our page on What is Coaching? for more about this) suggests that it may be hard to identify gaps in your own knowledge.

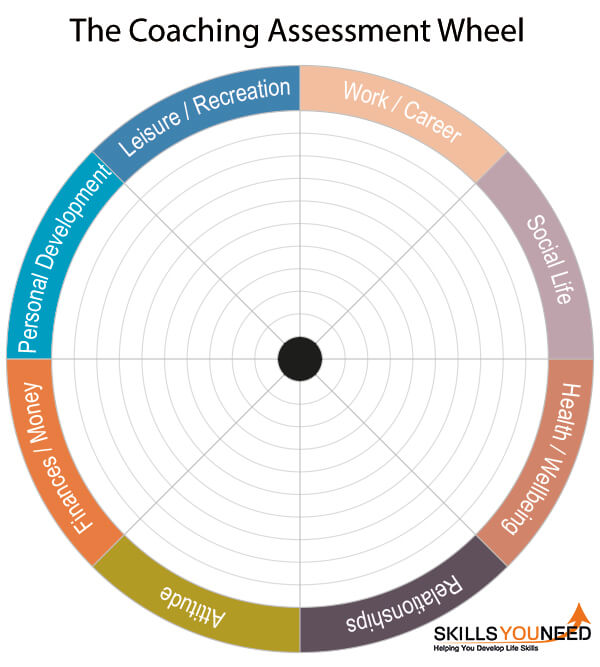

One way is to use an assessment tool. One that many coaches find useful is based on the ‘Wheel of Life’:

The headings for each segment are not fixed: you and the person you are coaching should together decide what to look at. They should reflect what that person wishes to consider in their coaching, and their overall goals.

You might, for example, concentrate on eight competences that are important for them at work, or they might want to include ‘work–life balance’ and ‘relationships’ to ensure that work is not the only aspect considered. For sports coaches, there may be specific areas that are important, such as nutrition, training time, skills, and downtime.

You do not need to use all eight segments, though it is advisable to use no more than eight.

Using the Coaching Assessment Wheel

The coachee should always complete the assessment wheel. If the coach knows them well—for example, where they are in a line management relationship—it may also be helpful for them to complete it, focusing on the coachee.

First, consider the ideal in your field. Who is the person that the coachee aspires to be? It is often easier to use a real person for this, because it makes the answers more honest and realistic. You can use more than one person as your ideal, for different aspects.

Then, for each segment, score your ideal out of 10. Be honest: scoring 10 for everything is unlikely to help you in the longer term! Consider what is really important and why.

Go through each segment and score the coachee out of 10.

Finally, compare the coach and coachee’s scores for each segment, and against the ideal. This will identify areas for discussion and potential work. It may, for example, surface ‘blind spots’ in the coachee’s awareness (both positive and negative). It should also identify elements for coaching, for example, where the ideal is an 8 or 9, and the coachee scores 2 or 3.

Further Reading from Skills You Need

The Skills You Need Guide to Coaching and Mentoring

Coaching and mentoring require some very specific skills, particularly focused on facilitating and enabling others, and building good relationships. This eBook is designed to help you to develop those skills, and become a successful coach or mentor.

This guide is chiefly aimed at those new to coaching, and who will be coaching as part of their work. However, it also contains information and ideas that may be useful to more established coaches, especially those looking to develop their thinking further, and move towards growing maturity in their coaching.

A Cautionary Note

Great coaches and coaching leaders are pleased, if not delighted, when the person they are coaching achieves something.

This sounds obvious but in practice, and especially if you’re a leader rather than an external coach, you may well feel a niggle of doubt: ‘Maybe they’re actually better than me?', 'Perhaps I’d better put them down a bit and keep them in their place?’. Strive to overcome this.

Remember that a great leader uses their team’s skills to balance their own. A really good coaching leader can develop a highly skilled team, and this is a sign of real strength. After all, a team should be greater than the sum of its parts.

The team’s glory will reflect on you as leader and support your own self-belief: “Look at me, I’ve built a great team and together this is what we’ve achieved!”

Finally...

If you’re ever tempted to put someone down because you think they may be reaching a level of expertise beyond yours, remember the adage that:

You should always be nice to those you meet on the way up,

because you may well meet them again when you’re on the way down!

More on Coaching:

What is Coaching?

Coaching at Home