Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder

See also: Understanding Other PeopleAutism spectrum disorder is a developmental disability that affects how people communicate and interact with the world around them. It affects how people operate and behave in various different areas, including social awareness, physical movement, sensory awareness and information processing. People with autism therefore show different symptoms and behaviours, although they may also have some in common with other people with autism.

The condition is relatively common. It is estimated to affect more than 1% of people in the world—which means more than 700,000 people in the UK alone. However, these are very much just estimates, and many people with autism find it very hard to get a diagnosis, never mind any treatment or support.

The Autism Spectrum

It may be helpful to discuss the autism spectrum, and explain what this phrase means, because it is widely misunderstood.

It is relatively common for people to say things like ‘Oh, we’re all a little bit autistic’, or ‘We’re all on the spectrum somewhere, aren’t we?’

To do so fundamentally misunderstands the nature of the autism spectrum, and instead treats it as if it were a gradient. It is worth unpicking this a bit more.

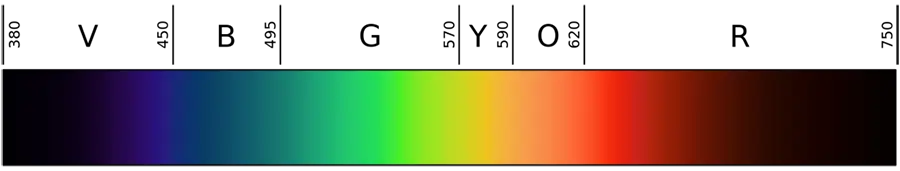

The website neuroclastic.com has a very good article explaining this issue, written by C. L. Lynch, called “Autism is a Spectrum” Doesn’t Mean What You Think. Lynch uses the spectrum of visible light as an example:

She points out that nobody would say that red is more blue than blue, or that blue is ‘more spectrum’ than red. We also don’t talk about colours being on the ‘low’ or ‘high’ end of the spectrum. You can’t say ‘Blue is more severe than red’, or ‘Yellow is less serious than green’.

Colours are just different, not ‘more’ or ‘less’.

A gradient, on the other hand, varies from lighter to darker, or less severe to more severe:

It is therefore possible to say that one end or the other is ‘more blue’ or ‘less blue’.

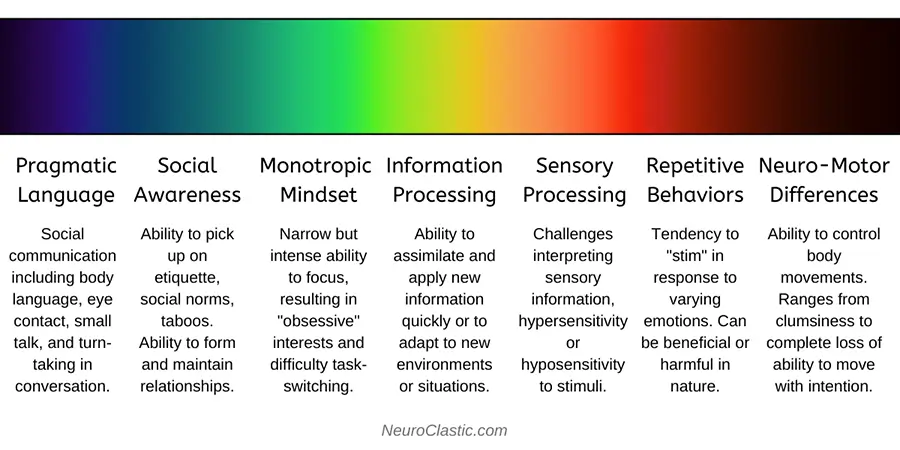

Using the same imagery, here’s what the autism spectrum might look like—different colours representing different aspects of processing or behaviour:

Autistic people tend to be affected in some way or another across ALL these aspects. If someone has problems or difficulties in just one area, then they are not autistic. They may have another condition—for example, problems with neuro-motor issues could be dyspraxia, and problems with processing information may be dyslexia. However, they are not ‘a little bit autistic’.

You can see how ridiculous it seems, therefore, when someone says “we’re all a little autistic” because they also hate fluorescent lights or because they also feel awkward in social situations. That’s like saying that you are dressed “a little rainbowy” when you are only wearing red.

C. L. Lynch, “Autism is a Spectrum” Doesn’t Mean What You Think, neuroclastic.com

It is also not reasonable to describe someone as ‘high-functioning autistic’ because their language skills are ‘normal’, or because they don’t need physical help to move around the world. Difficulties in different people with autism manifest in different ways across the spectrum—but they all have autism. Their difficulties are all disabilities, even if some are more hidden than others. Some areas of the spectrum are simply more outwardly obvious than others.

Behaviours, Signs and Symptoms of Autism

There are some popular stereotypes about people with autism, some of which are more justified than others. Rainman is really not the full story...

Some of the signs, symptoms and behaviours associated with autism include:

Social communication issues

Social communication is recognised as a challenge for many people with autism. The common stereotype is struggling to make eye contact, or taking language very literally. Both of these may be true. Fundamentally, many autistic people find it hard to interpret both verbal and non-verbal language. For example, they may not ‘get’ sarcasm, or appreciate the difference expressed by a change in tone of voice. They may also find it hard to understand abstract concepts, or not understand how to ‘do’ small talk or general conversation.

Social interaction issues

Autistic people often have trouble understanding others’ emotions and feelings, or expressing their own. They may therefore seem insensitive, or behave in ways that are considered inappropriate by others. This means that they often find it hard to make friends.

Repetitive behaviour and routines

Autistic people often like to build and use routines for everyday activities. They may prefer to travel to work or school by the same route each day, or eat exactly the same thing. Disruption of these routines can be very distressing. They may also use repetitive behaviour such as rocking or twirling a pen as a way to soothe themselves.

Sensitivity to sensory inputs

People with autism may have very different levels of sensitivity to different sensory inputs from neurotypical people. However, these may also vary widely between autistic people. Some people might be over-sensitive to some stimuli; others may be under-sensitive. Places with a lot of loud background noise, or bright lights, or too many people, may therefore cause a sensory overload.

Highly focused on certain hobbies or interests

Many autistic people, like people with ADHD, may develop an intense interest in particular areas of interest. This can drive them to achieve serious academic or popular success in that area—but it can also lead them to neglect other areas of their lives.

Anxiety

Many people with autism experience extreme anxiety about particular situations or places, often involving change. This can have a real impact on quality of life, including for the families of autistic people. Anxiety may need treatment by mental health professionals—but it is often hard for people with autism to access these services.

Meltdowns and shutdowns

This is perhaps the other area that is most stereotypically ‘autistic’. People with autism may go into meltdown or shutdown when things get too much—too much sensory overload, too many people. In each case, the response is the whole system shutting down, but in different ways. People in meltdown lose behavioural control, either verbally, physically or both. They may therefore shout, scream, kick, punch or all of these. People who shutdown simply cannot react anymore. It looks like they are going quiet, but it can be as debilitating and exhausting as a meltdown for the person concerned.

Getting a Diagnosis

As with many developmental disorders and specific learning difficulties, a diagnosis requires an assessment.

Your first step is therefore to talk to your family doctor, or any other health professional that you see regularly, such as a paediatrician, health visitor, or even dentist. For a school-age child, you can also talk to the Special Educational Needs Coordinator (SENCo) at the child’s school. They can all refer your child for an assessment.

TOP TIP! Make a list

It is a good idea to make a list of symptoms and signs before speaking to your healthcare professional. This will ensure that they have all the information so that they can make a sensible decision about whether an autism assessment is justified.

An autism assessment will usually be carried out by a team of professionals. They are likely to watch interactions, ask about problems, and speak to other people who know you or your child, including healthcare professionals, teachers, family and friends.

A diagnosis may be necessary to get help and support from a school or workplace, to enable you or your child to manage.

Support for People with Autism

Everyone with autism is different, and has different needs and problem areas.

The support that they need will therefore also be different. It is important to identify what support is needed and will be helpful.

It is also important to work with places like schools and workplaces to get the right support and accommodations in place. Generally, schools are expected to make efforts to meet the needs of learners, including those with autism. However, sadly this is not always what happens in practice. You may need to seek extra support from voluntary organisations such as the National Autistic Society (autism.org.uk) or Ambitious About Autism (ambitiousaboutautism.org.uk). However, the process of getting help in place can be long and hard.

A Long Road

The difficulties getting help for children with autism are encapsulated in the social media handle of one mother with two autistic children, who posts on Facebook as ‘The Long Road – a Diary of a SEND Mum’.

A Final Thought

Like other forms of neurodivergence, autism cannot be ‘cured’—and nor should we be thinking about that as an ambition.

Instead, we should be asking how the world can change to better accommodate everyone, not just neurotypical people—and how we as individuals can help to make that happen.